Moving chemicals can actually be the most dangerous part of handling them. When a bottle is sitting on a shelf, it is safe and stable. But the moment you pick it up, you invite risks like tripping, dropping it, or sudden stops in traffic.

Because of these unpredictable dangers, safety experts see way more spills happen during transport than during storage. That means we can't just rely on luck; we need a solid game plan.

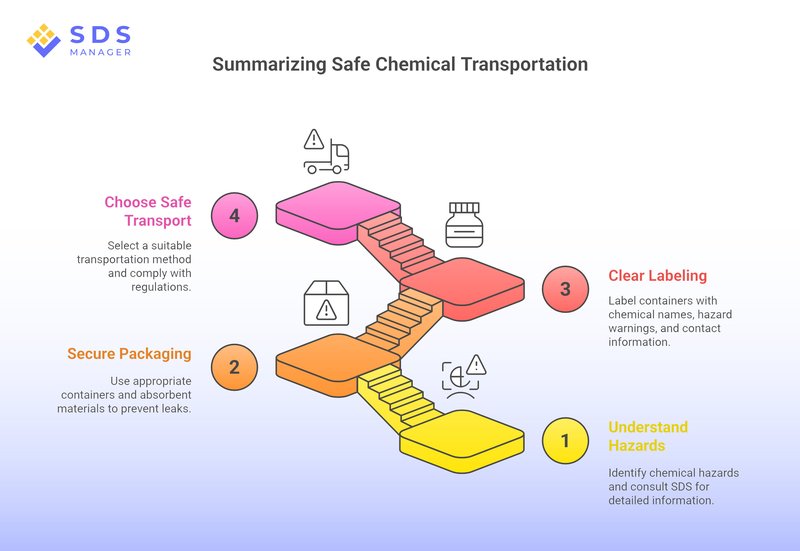

The safest way to transport chemicals isn't about memorizing a textbook, it can be as simple as following a four-step plan that helps you transport chemicals, preventing incidents.

Steps you can follow to Transport Chemicals Safely

Step 1: Check Your Safety Data Sheet

Before you even touch a container, you need to know exactly what you are dealing with. The best way to do that is to check the Safety Data Sheet (SDS).

You can think of the SDS as the instruction manual for that chemical. Different sections answer different questions:

- Section 2 (Hazard identification) tells you what kind of hazards the product has – for example, whether it is flammable, corrosive, toxic, or dangerous to the environment, and what warning statements and pictograms apply.

- Sections 9 and 11 give more detail about physical and chemical properties and toxicology, if you need a deeper look.

- Section 14 (Transport information) explains how the product is classified for transport: its UN number, proper shipping name, transport hazard class, packing group, and notes for moving it by road, rail, air, or water.

A simple approach that works well is to check Section 2 first, so you know how dangerous the chemical is, then look at Section 14 to see how it should be treated during transport.

This quick review helps you decide whether you need extra protection, smaller quantities, or help from your safety team or a trained shipper.

Pro Tip: Ask yourself, “Do I really need to move my product in such a big amount?” If you can transport a smaller amount, you lower the risk straight away.

Step 2: Keep chemicals in double-layered containers

Most transport accidents come down to the same few problems: a bottle cracks, a cap loosens, or a container tips over. To keep that from becoming a serious incident, you use secondary containment – in everyday language, double-packing.

First, make sure the original container is sound: no cracks, no corrosion, and a tight cap. Then put that container inside something tougher, like a plastic carrier, tray, or bin.

The guiding idea is simple: the outer container should be able to hold all of the chemical if the inner one fails. If a glass bottle breaks when a cart hits a bump, the liquid should end up in the tray or bucket, not on the floor of the hallway or vehicle.

Most businesses dealing with many chemical products need to transport several products at once. In such cases, do not throw everything into one bin.

Keep incompatible chemicals apart – for example, acids separate from bases, and oxidizers away from fuels or solvents. A basic compatibility chart from your safety team makes this much easier to manage.

Step 3: Label everything clearly

Picture a leaking box in a corridor or on the back of a truck, with no label. Nobody knows what is inside, how dangerous it is, or what to do next. That is exactly what you want to avoid.

Both the main bottle and any outer container used for transport should be clearly labeled with transport labels including:

- the name of the chemical, and

- its main hazards (for example: “corrosive acid”, “flammable solvent”).

When chemicals are being driven somewhere, even just across town, it is wise to have a simple piece of paperwork. This could be a short shipping document or transfer form that lists what you are carrying and an emergency contact number.

For larger or more hazardous loads, that information is based on how the product is described in SDS Section 14, which feeds into proper shipping names and UN numbers in formal transport paperwork.

Keeping a copy of the SDS nearby (printed or digital) adds another layer of protection. If something happens, you or a first responder can quickly see what the hazards are and what the recommended first steps should be.

Step 4: Use the right mode of transportation

Once the chemicals are packed and labeled, how you move them matters just as much.

Don’t use Personal Cars

Using a personal car is strongly discouraged. Most personal vehicles have no separate cargo space, limited ventilation, and no way to properly secure containers. If there is a leak, vapors can build up around you and your passengers.

Choose Safer Transport Options

A safer choice for road transport is a dedicated service vehicle, van, or truck where the load can be strapped down and kept away from the driver.

Regulations in New Zealand

For road and rail, dangerous goods must follow Land Transport Rule: Dangerous Goods 2005, which sets the legal requirements for packaging, identification, documentation, segregation of incompatible goods, transport procedures, and the training and responsibilities of those involved.

That rule works together with the technical standard NZS 5433: Transport of dangerous goods on land, which provides detailed good-practice guidance on how to classify goods, choose packaging, and use UN numbers and proper shipping names.

Dangerous goods rules fit into a wider hazardous substances system. Hazardous substances are controlled across their full lifecycle under the main hazardous substances law and its Health and Safety at Work (Hazardous Substances) Regulations, with the Environmental Protection Authority handling approvals and classifications and WorkSafe focusing on workplace safety.

For other modes, there are separate but linked rules: dangerous goods by air are covered by Civil Aviation rules on carriage of dangerous goods, and dangerous goods by sea are covered by maritime rules that align with the international dangerous goods code for ships.

The Most Common Mode of Transportation in Day-to-Day Operations

In day-to-day work, you will mostly see road transport, from small vans carrying lab waste to larger trucks with drums or totes. Some chemicals also move by rail or vessel over longer distances, and small, urgent shipments may go by air.

Even though the details differ, the core ideas are the same in each mode: strong packaging, clear labeling, trained people, and a plan if something goes wrong.

Move Safely Inside Buildings

Inside a building, your “transport vehicle” is usually a cart. Choose one with raised edges so containers cannot slide off, and push the cart at a steady pace rather than rushing.

One small but important habit: if you wear gloves while handling containers, keep one hand ungloved for opening doors and pressing elevator buttons. That way, you are not leaving invisible chemical residues for the next person to pick up.

Final thoughts

Taking chemicals on the road doesn't have to be a stressful experience. It really just comes down to taking the guesswork out of the equation by following a steady routine:

- Understand the hazards

- Pack so leaks stay contained

- Label clearly

- Choose a safe way to transport your chemicals.

When you rely on these simple rules instead of luck, you build a safety net that protects you even when things don't go exactly as planned.

Once that becomes a habit in your lab, shop, or warehouse, chemical transport becomes predictable, calmer, and much safer for everyone involved.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What documents should travel with chemical shipments?

A list of products, quantities, and an emergency contact, plus access to the SDS. Dangerous goods on land usually need a transport document based on the Land Transport Rule and SDS Section 14 details.

2. Can I use my personal car to move chemicals?

Generally no. Personal vehicles are not designed for chemical or dangerous goods transport. Use work vehicles or approved carriers and check with your safety team or transport adviser.

3. How do I keep incompatible chemicals apart during transport

Use a compatibility chart and keep different groups in separate trays or compartments so they cannot mix if something leaks.

4. What kind of packaging is safest?

For small amounts, sealed containers with sturdy secondary containment. For larger loads, use approved drums, IBCs, or tanks that meet the relevant land transport and NZS 5433 requirements.

5. Why is transport seen as riskier than storage?

Transport involves moving, loading, and unloading, so containers are more likely to be bumped or stressed than when they stay in long-term storage.